Personal tools

News from ICTP 95 - Features - IMSP

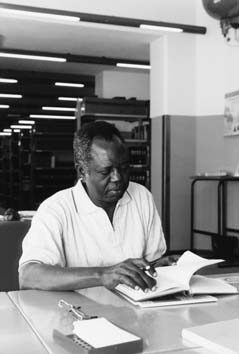

Jean-Pierre Ezin, who has been associated with ICTP for more than two decades, describes how he hopes his Institut de Mathématiques et de Sciences Physiques will become a major regional math and physics centre in West Africa.

Into Africa

Jean-Pierre Ezin

When the first parcel of earth

was turned last spring to begin construction of a regional math

centre just outside Benin's capital city Porto-Novo, it marked

the end of a 25-year campaign for the construction of a regional

research and training facility in this small poor country on the

west coast of Africa. Jean-Pierre Ezin, a long-time visitor to

ICTP and head of the University of Benin's Institut de Mathématiques

et de Sciences Physiques (IMSP), has witnessed--indeed directly

participated in--the entire saga. In his own words, "the

ground breaking ceremony was a proud moment; now the real work

begins."

"I was a young post doctorate student at ICTP in the mid

1980s," explains Ezin, "when Abdus Salam asked me if

I would be interested in having ICTP support two or three students

when I returned to the University of Benin's math department to

resume my teaching responsibilities after a two-year hiatus in

Trieste."

"I was honoured by Salam's offer but I responded that the

creation of an independent centre, with its own research and training

responsibilities separate from the university's, might have a

greater long-term impact on the growth of mathematics in Benin.

To my surprise, Salam quickly concurred and assigned US$25,000

in the ICTP's budget to launch the effort. Salam also helped convince

the government of Benin to match ICTP's contribution." The

result was the creation of IMSP.

"The initiative, while modest, did fulfil some of the goals

both Salam and I had hoped for," says Ezin. "The first

US$25,000 grant from ICTP, given in 1989, turned into an annual

contribution that has continued to this day. Over the past decade,

the money has enabled us to enrol five students every other year

to participate in our advanced degree programmes in math and physics."

Additional periodic funding--for example, from Belgium, France

and Germany--has allowed the institute to raise its enrolment

at times to as many as 10 or 15 students. But it's ICTP's consistent

year-to-year funding, derived from the Centre's Office of External

Activities, that has given the Benin institute a firm foundation

from which it has developed into one of the most respected institutions

of its kind in Africa.

The institute was the first ICTP Affiliated Centre, an initiative

that has since become the centrepiece of ICTP efforts to work

jointly with universities and research centres in developing countries

to establish reputable in-country training and research facilities

serving local and regional scientific communities in a wide range

of disciplines. These centres, based on agreements between ICTP

and the host institutions, are found throughout the developing

world.

Today, there are six ICTP Affiliated Centres in Africa: IMSP in

Benin; a centre on semiconductors, solar cells and quantum physics

in Ethiopia; laser centres in Ghana and Sudan; and atomic physics

centres in Senegal and Cameroon. Each receives an annual grant

of about US$25,000 from ICTP.

The first class of five students at IMSP in Benin, all of whom

began in March 1989, attained their doctorates by 1994. All have

since gone on to successful academic careers. Isso Ramadhani,

who is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, now teaches

at the University of Kinshasa, and Bernard Kamte, who is from

Cameroon, teaches at the University of Toronto. Meanwhile, the

institute's first three students from Benin have remained in their

home country--Jean Bio Orou Chabi and Joël Tossa are employed

at their alma mater and Taofick Adeleke at the Institut National

d'Economie. The 25 plus students who have followed in their

footsteps have achieved similar levels of success.

"We are not only pleased by our graduation rates, which have

been exceptionally high," explains Ezin, "but we are

proud that many of our graduates have continued to work in Africa--often

in their native countries--after attaining their degrees."

Ezin attributes this encouraging trend, which runs counter to

the 'brain-drain' effect that has sapped the strength of many

other like-minded initiatives, to the way in which his programme

has been structured.

"Our doctorate programme," he explains, "has always

followed the so-called 'sandwich' model: Students spend their

first year or two at IMSP, then move on to a university in the

North for a year or two, only to return to the University of Benin

to complete their course work and thesis. This way, students never

lose touch with IMSP. As a result, they are less likely to wind

up as professors or researchers in institutions in the developed

world."

IMSP works closely with a number of Northern universities and

research centres to ensure that the goals of its 'sandwich' programme

are met: for instance, in Belgium, the Université Libre

de Bruxelles; in Canada, the University of Toronto; in France,

the Université de Paris Sud in Orsay; in Germany,

the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics; and in the United States,

Florida State University. "All told," Ezin notes, "the

institute's sandwich programme involves more than a dozen institutions

in the developed world."

Overall, IMSP's track record of success has meant a great deal

to the math and physics community in Africa, where advanced training

and research facilities are in short supply and where many universities

do not even have a single math teacher with a doctorate degree

(see "Africa's

Future Discounted by Math Crisis," News from ICTP,

Summer 1998, p. 6-7).

Ezin and others who have been involved in the field for many years

have always realised that the number of doctorates that institutes

like his have been able to produce--some five Ph.D.s every other

year--are no match for the magnitude of the math and physics crisis

faced by Benin and other nations in Africa. "I don't want

to minimise our contribution," says Ezin, "but the truth

is our efforts have largely prevented a very bad situation from

getting much worse. We've never had sufficient resources to make

a great deal of progress. The best we've been able to do is to

prevent additional backsliding."

That may change, however, now that the government of Benin has

agreed to invest US$1 million for the expansion of IMSP. The new

support represents such a large increase--the institute's current

annual budget is just US$50,000--that, in effect, the allocation

sets the stage for the creation of a new institute different not

only in size but in scope from the facility that has preceded

it.

"This substantial infusion of funding," Ezin notes,

"should allow us to provide instruction for some 100 students

each year, not five every other year, which is the current situation."

To achieve this goal, Ezin anticipates that the number of faculty

will eventually increase from seven to 20.

"As our resources and size grow, so will the breadth and

depth of our curriculum," explains Ezin. "The institute

plans to offer courses in differential geometry, statistical physics,

functional analysis, control and game theory, and computer science.

We also plan to eventually build exchange programmes with other

math and physics institutions both in Africa and on other continents.

In fact, I have had preliminary conversations with colleagues

in Latin America that we hope will soon lead to some joint training

and research activities."

IMSP construction site

It's all part of an ambitious agenda that includes new classrooms,

a library, cafeteria, and guesthouse. "The goal is to build

a mini-ICTP-like facility designed primarily to serve the needs

of young mathematicians and physicists in West Africa," says

Ezin, who views what is happening "as an extension of Salam's

vision, which could never be completely realised until governments

in developing countries begin to invest in scientific research

and training effectively and sustainably."

So, after decades of coaxing and cajoling by Salam, Ezin and dozens

of others dedicated to the development of science in the South,

the Institut de Mathématiques et de Sciences Physiques

in Benin may soon emerge as an enduring symbol of their hard work

and dedication-and, more importantly, as an institution that helps

build a strong foundation in basic science that lifts the economic

and social well-being of the entire region.

IMSP construction site